Cuff Deflation

Cuff Deflation for a Tracheostomy Tube

Deflating the cuff of the tracheostomy tube has many benefits for a patient with tracheostomy, but must be done with caution. Cuff deflation is a necessary stage in the decannulation process. In one study 95% (107/113) patients were able to achieve cuff deflation on the first attempt. Medical stability, respiratory stability and the amount of above the cuff secretions (less than 1ml/hr) were the main indicators for successful cuff deflation (Pryor, L et al, 2016).

For information specific for patients with COVID-19 for cuff deflation please see COVID-19 and Tracheostomy and Mechanical Ventilation.

Purpose of the tracheostomy cuff

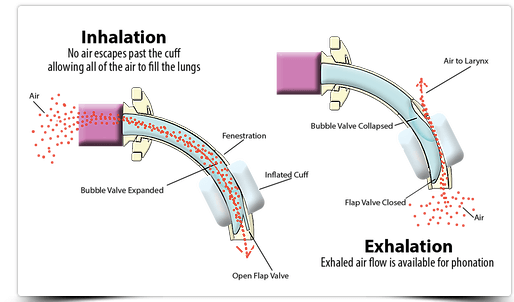

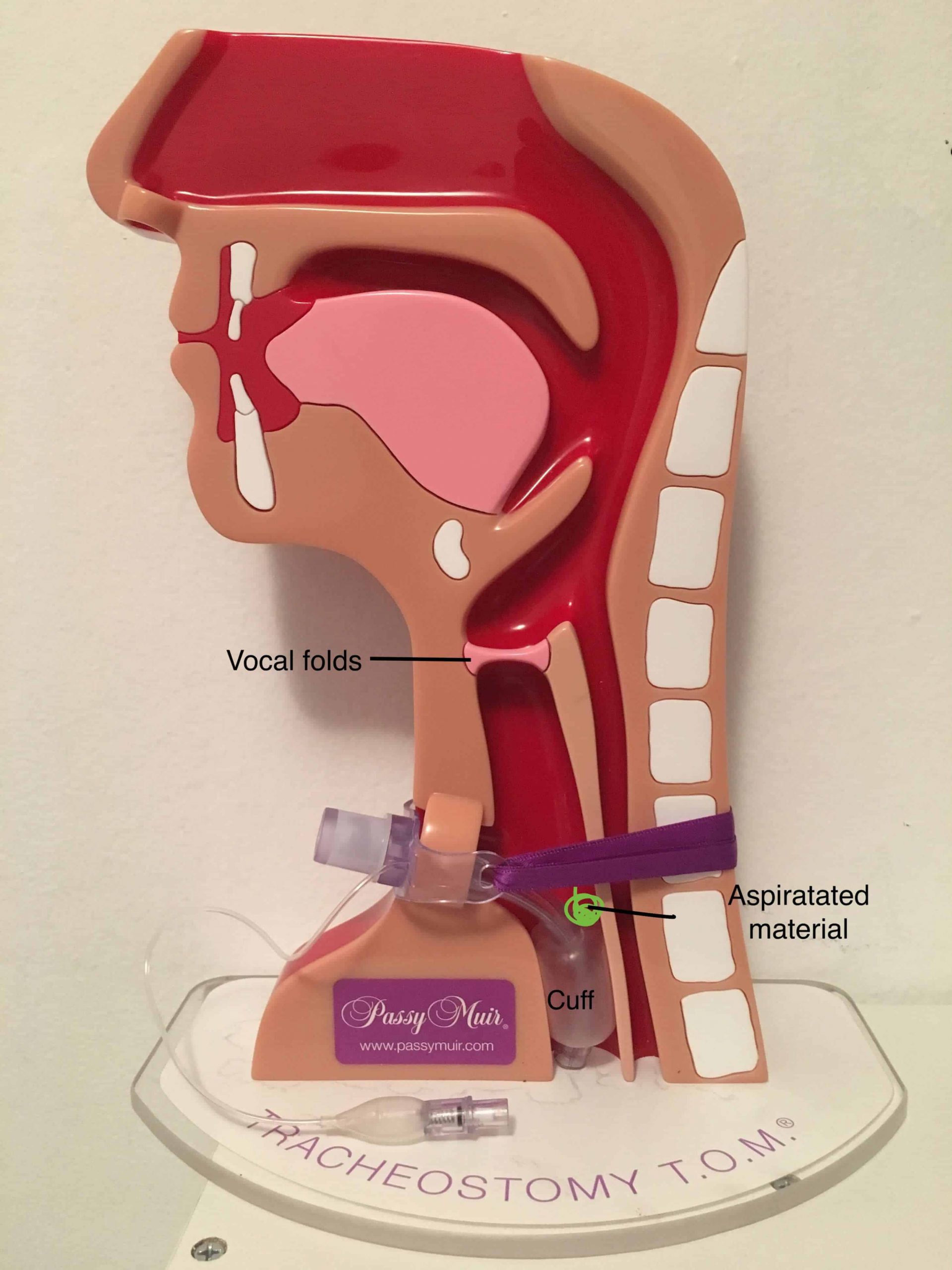

The purpose of the cuff is to maintain the air delivered from the mechanical ventilator to the lungs. The cuff fills the tracheal space around the tracheostomy tube to prevent airflow from escaping around the tube and through the upper airway. Instead, airflow is directed through the tracheostomy tube, which allows the ventilator to control and monitor ventilation for individuals on mechanical ventilation. Therefore, positive pressure ventilation can be applied more effectively when the cuff is inflated. However, many individuals on mechanical ventilation can be managed with the cuff deflated or cuffless tracheostomy tubes.

The tracheostomy cuff and aspiration

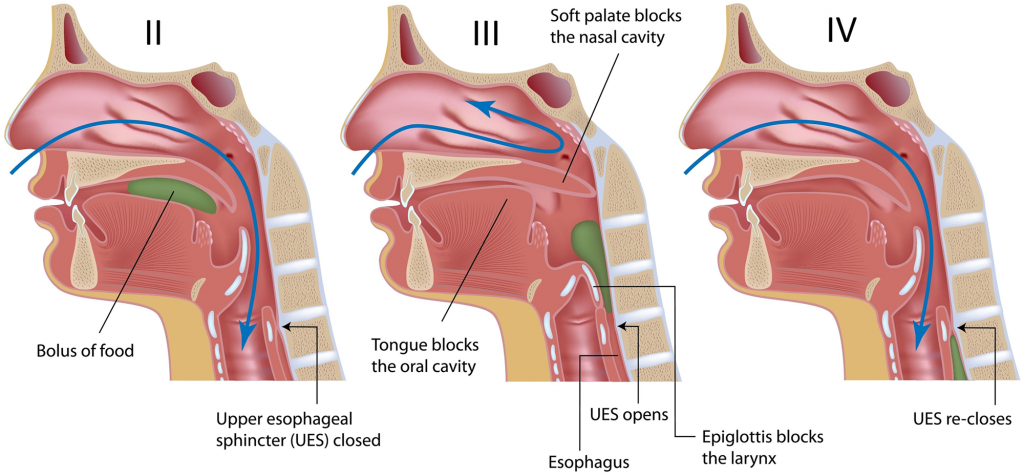

Material above the cuff is already aspirated

- Once the cuff is deflated, aspirated material can fall into the lungs.

- Material that pools on top of the cuff may result in inflammation of these tissues (Siebens et al, 1993) and has potential to colonize as a source of infection.

- Cuffs do not form an airtight seal against the trachea wall, therefore allowing material to pass around the cuff and into the lower airways and lungs.

On rare occasions, there are patients who have severe swallowing impairments and difficulty managing secretions who may have difficulty tolerating cuff deflation. These patients are unable to tolerate cuff deflation noted by a significant change in vital signs or respiratory distress during cuff deflation. An inflated cuff can provide a means of bypassing the secretions that are unable to be cleared during cuff deflation through the upper airway.

Complications of the Cuff

Complications of an inflated cuff include gram negative colonization and infection from material that has pooled above the level of the cuff. Secretions above the cuff are not accessible to tracheal suctioning. Subglottic suctioning is an option, but not always available. If secretions above the cuff are not removed, they have the potential to harden and form a mucous plug which can easily fall into the bronchi causing an obstruction and result in possible atelectasis, pneumonia or death. The cuff is also associated with a risk of tracheomalacia, tracheoesophageal fistula, pneumothorax, subcutaneous emphysema, tracheal stenosis, and bleeding. For more information see Complications of Tracheostomy.

Benefits of Cuff Deflation

When the cuff is deflated, some airflow is reestablished through the upper airway. There is movement of airflow both through the tracheostomy tube as well as through the upper airway. This increases the effective airway diameter. If sufficient airflow passes through the vocal folds, this will allow for the vocal folds to vibrate and result in phonation. Bach et al. [16] previously suggested that increasing the effective ventilatory tracheal cross section was the only way to achieve successful disconnection from mechanical ventilation in patients with marginal ventilatory reserve (Bach et al, 1990).

- In a randomized study of critically ill patients, weaning time was shortened in the cuff deflated group compared to the cuff inflated group [3 (2–4) vs. 8 (6–10) days] (Hernandez, G et al 2013).

- Aspiration rates are lower when feeding patients with the cuff deflated versus inflated. Aspiration rate has been shown to be 2.7 times lower for cuff deflation versus cuff inflation conditions within the same patient (Davis et al, 2002).

- Silent aspiration rates during oral intake have been shown to be less when the cuff is deflated, likely due to restored sensation and cough reflex. In a retrospective study, silent aspiration rates were 7.2% for cuff deflated and 22.6% for cuff inflated condition (Ding, R. & Logeman, J, 2005). This may indicate pharyngeal and laryngeal sensation improve when the cuff is deflated.

- There are lower rates of respiratory infections when the cuff is deflated. In a randomized controlled study of critically ill patients, the cuff deflated group had significantly less respiratory infections including ventilator-associated pneumonia with rates of 20% versus 36% cuffs inflated (Hernandez, G et al 2013).

Cuff Deflation Procedure

- Explain the procedure to the patient as appropriate. Explain that they may experience movement of airflow and secretions through the upper airway and a possibility of producing voicing. An anatomical drawing of the airway with the cuff inflated and deflated may help the patient to understand the process.

- Monitor the patient’s vital signs during cuff deflation, particularly when it is the initial time.

- If vitals are stable, next suction via the mouth and/or stoma as necessary to remove any secretions prior to cuff deflation. If available, above the cuff suctioning can be utilized.

- Connect the syringe to the pilot balloon and slowly remove air (perhaps 2cc of air at a time) from the syringe. This removes air from the cuff of the tracheostomy tube.

- Perform tracheal suctioning while deflating the cuff to attempt to remove secretions that have passed into the lower airways, preventing them from falling into the lungs. The cuff can be fully deflated or partially deflated for leak speech.

- Assess the patient’s tolerance of cuff deflation and reinflate the tracheostomy tube if any distress or significant changes in vital signs.

Cuff Deflation While on Mechanical Ventilation- Leak Speech

Some practitioners may be hesitant to try managing mechanical ventilation in the cuff deflation condition, concerned that adequate ventilation cannot be maintained. In a study done on “unweanable” patients with mechanical ventilation with neuromuscular disease, Bach reported that 91 out of 104 patients were adequately ventilated with either the cuff deflated or with cuffless tracheostomy tubes (Bach & Alba, 1990). Pediatric patients are typically ventilated with cuffless tracheostomy tubes in order to reduce complications of inflated cuffs.

The cuff may be deflated when an individual is on mechanical ventilation in order to allow for speech and improved swallowing. The term used to describe speech when the cuff is fully or partially deflated is termed “leak speech.” Speech is primarily available on the inspiratory cycle as this is the phase when the ventilator primarily delivers air. . With the conventional volume-control mode, patients use the pressures and flows provided by the ventilator to speak. Ventilator-supported speech is therefore mainly produced during the inspiratory phase of the ventilator cycle and can only be continued during the initial part of the expiratory phase, as it stops when the tracheal pressure falls below the threshold value allowing speech.

When cuff deflation is performed with volume modes, the airflow used to ventilate the patient is partly being used for speech. Ventilator changes may improve tolerance of cuff deflation for those on mechanical ventilation.

After step six in the above protocol, assess the patient for possible ventilator changes. A physician order is required prior to ventilator changes.

Volume: The patient may not receive the pre-set tidal volume when the cuff is deflated. Tidal volume may need to be increased in order to compensate for the loss of volume that occurs through the upper airway during cuff deflation. Excessive tidal volume may lead to barotrauma, particularly in those with high peak inspiratory pressures to begin with. Increasing tidal volume should be done slowly with no more than 400ml of additional volume provided.

I:E Ratio: The I:E ratio is the ratio of inspiration to expiration. Increasing the inspiratory time can be achieved by lengthening the set inspiratory time (iTime) or lowering the inspiratory flow rate. Increasing the amount of time of inspiration can provide longer speech (syllables per minute)(Hoit et al, 2003) and may also improve patient comfort. This may help the patient to coordinate voice with the ventilator.

Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP): If the PEEP is set to zero than most of the exhaled gas will exit through the ventilator circuit rather than through the upper airway, resulting in limited ability to speak during expiration. When PEEP is set on the ventilator then there is an increased likelihood that gas will flow through the upper airway, which increases speaking rate. When PEEP was added (5 to 10 cm H(2)O), speaking time was 25% longer and obligatory pauses were 21% shorter (Hoit et al, 2003). Patients are able to speak but on inspiration and expiration when changes to inspiratory time and PEEP were made. This is different than normal speech, which occurs on exhalation only. High PEEP levels may result in hyperinflation, but is easily adjustable to patient tolerance.

Bilevel Positive Pressure Ventilation (BPPV) combines PEEP and Pressure Support Ventilation (PSV), thus providing an increase in Ti and tidal Volume (iV) during leak speech, which allows the combination of beneficial effects on speech production of adding PEEP and changing iTime without manual adjustments. Most pressure-support devices, terminate inspiration when inspiratory flow falls below a set percentage of the inspiratory peak flow. Patients subjectively felt more comfortable speaking on BPPV than ACV (Prigent, H et al, 2003).

Instruction in Glottic Control

Once the patient has the cuff deflation, the clinician can instruct in glottic control such as attempting to close the vocal folds to allow for airflow to maintain in the lungs. An in-line speaking valve may be attempted once the cuff is completely deflated to allow for improved speech. See our section on ventilator application of speaking valves.

-

Tracheostomy Manikin

Rated 5.00 out of 5$1,895.00 Select options -

Sale!

Children’s Tracheostomy Book Hardcover | Trachie-O-Potamus’s Big Race

Rated 5.00 out of 5$24.99$21.99 Add to cart -

Evidence-Based Swallowing Evaluation for Patients with Tracheostomy and Mechanical Ventilation Webinar

Rated 5.00 out of 5$40.00 Add to cart

Summary

Cuff deflation may benefit a patient for improving speech and swallowing, but must be done cautiously and for patients deemed medically stable. A physician order is required prior to cuff deflation.

Related Webinars

Resources

Davis, et al. (2002) Swallowing with a Tracheotomy Tube in Place: Does Cuff Inflation Matter? Journal of Intensive Care Medicine.17(3): 132-135.

Ding, R. & Logeman, J. (2005). Swallow Physiology in Patients with Trach Cuff Inflated or Deflated: A Retrospective Study. Head & Neck. Sep;27(9):809-13

Ehsanian, R, Klein, C; Mohole, J, Colaci, J, Pence, B, Crew, J, McKenna, S. A Novel Pharyngeal Clearance Maneuver for Initial Tracheostomy Tube Cuff Deflation in High Cervial Tetraplegia. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation: Aprl 2019.

Hernandez, G. et al. (2013). The effects of increasing effective airway diameter on weaning from mechanical ventilation tracheostomized patients: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Medicine. Jun;39(6):1063-7

Hoit JD, Banzett RB, Lohmeier HL, Hixon TJ, Brown R. Clinical ventilator adjustments that improve speech. Chest 2003;124(4):1512–1521. CrossRefPubMedGoogle Scholar